Radical

Statistics

Explanations for growth of sole parent benefit numbers in the 1970s in New Zealand

Kay Goodger

Editors' note. The recent furore over cuts in state benefits for lone parent families by the British Labour government demonstrated the political sensitivity of policy in this area. This article, excerpted by the author from a longer article on lone parent policy in New Zealand (rates Goodger, 1998), examines the way in which statistics about lone parents were misused in order to legitimate cuts in their benefit - Domestic Purposes Benefit (DPB).

Numbers on DPB grew rapidly after its introduction in 1973 (by over a third annually until 1976) and increasing steadily at 9 per cent pa on average. The rapid rise in numbers and expenditure prompted the government to order a review in 1976 to find the cause of the increase and to assess whether the provision of the benefit was influencing marital and reproductive behaviour. The recommendations of the DPB Review Committee (known as the Horn Committee) were based on incorrect and misleading statistics (Swain, 1977; 1979).

First, divorce rates were calculated by dividing the number of divorces in a particular year by the number of marriages celebrated in the same year, rather than the number of existing marriages. This greatly exaggerated the level of divorce and the increase over time, from '1 divorce per 12 marriages in 1965 [to] 1 per 5 in 1975'. The actual divorce rates for those years are: 3.1 per 1000 married couples in 1965 and 6.8 per 1,000 in 1975.

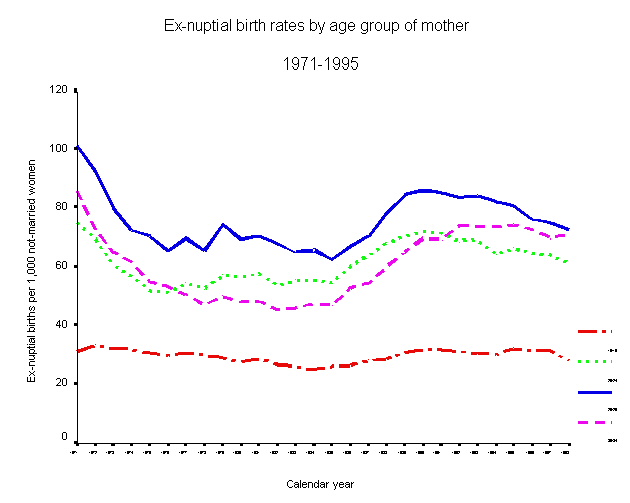

Second, the Horn Committee report used the ex-nuptial birth ratio (the number of ex-nuptial births per 100 total births) to assess changes in reproductive behaviour. This measure is affected by changes in marital fertility as well as fertility among the unmarried. During the 1970s, the ex-nuptial birth ratio was increasing but this was largely because marital births were declining. The ex-nuptial birth rate (the number of ex-nuptial births per 1,000 women who are not currently married) is a more appropriate measure of the fertility behaviour of single women. According to this measure, the likelihood of women having a birth outside marriage actually fell during the period in which DPB was introduced, from a peak of 44 per 1,000 in 1971 to 37 per 1,000 in 1976. Even among teenage single women, there was no rise in fertility in response to the introduction of the statutory DPB in 1973 (rates Figure 1).

On the basis of these misleading statistics, the Horn Committee concluded that the DPB produced substantial behavioural effects. The committee recommended a reduced rate of benefit for up to six months, to discourage couples from separating too readily and to reduce the supposed incentive for single women to keep their children rather than to have them adopted. However, this policy had no discernible effect on marital or reproductive behaviour; its main effect was to reduce the incomes of sole parents.

Figure 1 Ex-nuptial birth rates by age group of mother, 1971-95

Source: Statistics New Zealand, Demographic Trends 1996, Table 2.9

There is little evidence for the assertion that the introduction of DPB had a major influence on marital breakdown. There were several important changes in family law in the 1960s and 1970s that reflected, and may have influenced, changes in marital behaviour. The Matrimonial Proceedings Act 1963 introduced separation agreements, legitimising divorce by mutual consent for the first time. The 1968 amendment to this Act considerably shortened the time it took to get a divorce, reducing the waiting period attaching to several grounds from three to two years and reducing the period of living apart from seven to four years. The passage of this legislation was immediately followed by a 37 per cent rise in the divorce rate (from 3.5 per 1,000 in 1968 to 4.8 per 1,000 in 1969) and a 53 per cent rise in the number of new petitions for divorce. Trends in the number of divorce petitions filed illustrate the immediate impact of legislative change better than divorce rates (Figure 2). The rise in the divorce rate in 1974 is not attributable to the introduction of the statutory DPB in November 1973; rather it reflects the final stage of divorce proceedings that began in earlier years.

The introduction of legal aid in 1970 reduced the financial costs of divorce for spouses with low incomes. The Matrimonial Property Act 1976 guaranteed each spouse a half share in matrimonial property after divorce. In 1980, the Family Proceedings Act brought in 'no fault' divorce, the sole ground being irretrievable breakdown of the marriage, evidenced by living apart for two years. The Family Proceedings Act also effectively ended spousal maintenance. These reforms made divorce accessible to a wider range of people and increased certainty about its financial outcome, as did the introduction of the DPB.

However, the reasons for the increase in marriage breakdown that began in many countries in the 1960s cannot be explained by economic factors alone. Changes occurred in the characteristics of people marrying at that time (unusually young, often pregnant) and in values concerning individual autonomy, secularism and post-materialism (rates Lesthaeghe, 1995).

Figure 2 Divorce petitions and rates in relation to family law reforms, 1960-86

Sources: Statistics New Zealand, Demographic Trends 1996, Justice Statistics (various years)

ch of the rapid growth of DPB numbers in the early 1970s can be explained simply by the increased propensity for sole parents to take up social assistance, rather than rely on infrequent maintenance payments and low wages. This can be illustrated by the changing ratio of benefits of sole parents and deserted wives to the number of maintenance orders in place in the early 1970s (1). In 1971, there were 5,600 benefits being paid and 20,800 maintenance orders or agreements in place, a ratio of 27 per cent. Within six years, the number of benefits had risen to 29,000 while maintenance orders had risen less rapidly to 36,300, increasing the ratio to 80 per cent. This was an entirely predictable response, given that the aims of the policy were to reduce poverty among these families and support them while out of the workforce. But it was interpreted by the DPB review Committee as an increase in 'the problem' rather than an increase in 'the solution' (rates Swain, 1977)(2).)

The common perception that single mothers accounted for the majority of sole parents seeking assistance in the early 1970s is not borne out by the available statistics. The number of ex-nuptial children kept by single mothers between 1968 and 1976 was 20,908, while the number of unmarried DPB recipients in March 1977 was only 5,493. These figures suggest that many single mothers did not apply for the benefit, or that those who did so did not remain on the benefit for long. Many single mothers later married and adopted their children jointly with their spouse. The number of 'one parent and spouse' adoptions grew by 82 per cent between 1968 and 1976, by which time they made up 36 per cent of notified adoptions (rates DSW, 1977). In 1977, single mothers were a fifth of DPB recipients and that proportion remained stable for many years. Most of the growth of sole parent benefit numbers in the 1970s came from marraige breakdown. Between 1977 and 1982, sole mothers who had previously been married or cohabiting accounted for 79 per cent of the growth in DPB numbers; previously married sole fathers made up 5 per cent and single mothers 15 per cent.

Notes

- This is not an exact statistic as the receipt of a maintenance order often occurred at a later date than grant of benefit. However, the overall trend is clear.

- Swain (1977) made the comparison with the well-studied introduction of NHS subsidies for dentures and spectacles in the UK in the late 1940s, which produced a dramatic increase in take-up of the subsidy. He argued that attributing the increase in DPB numbers to a massive increase in marital breakdown was as logical as interpreting the increase in NHS subsidies as signifying the wholesale collapse of health and eyesight among British people.

REFERENCES

Department of Social Welfare (1977) Annual Report, Wellington: DSW.

Goodger, K. (1998) 'Maintaining sole parent families in New Zealand: An historical review', in Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 10(June).

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995) 'The second demographic transition in western countries: an interpretation', in K. Mason and A. Jensen (eds) Gender and Family Change in Industrialised Countries, Oxford: Clarendon.

Swain, D. (1977) 'Divorce in New Zealand', in New Zealand Listener, July 16th; September 10th (Letters to the Editor).

Swain, D. (1979) 'Marriages and Families', in R. Neville and C. O'Neill (eds) The Population of New Zealand: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Auckland: Longman Paul.

Kay Goodger, Researcher/Analyst

Social Policy Agency

Department of Social Welfare, Private Bag 21

Wellington,

New Zealand

tel: (64) 04 471 0321,

email: kayg@wn.planet.gen.nz